On the 1st of February 2026 APRA will change the DTI for all home buyers, investors or owner occupiers. Is this a similar move they did back in 2017? If so will this cause the property market to soften?

In our previous blog we discussed the changes and how to get around it, here we will discuss how it compares to 2017.

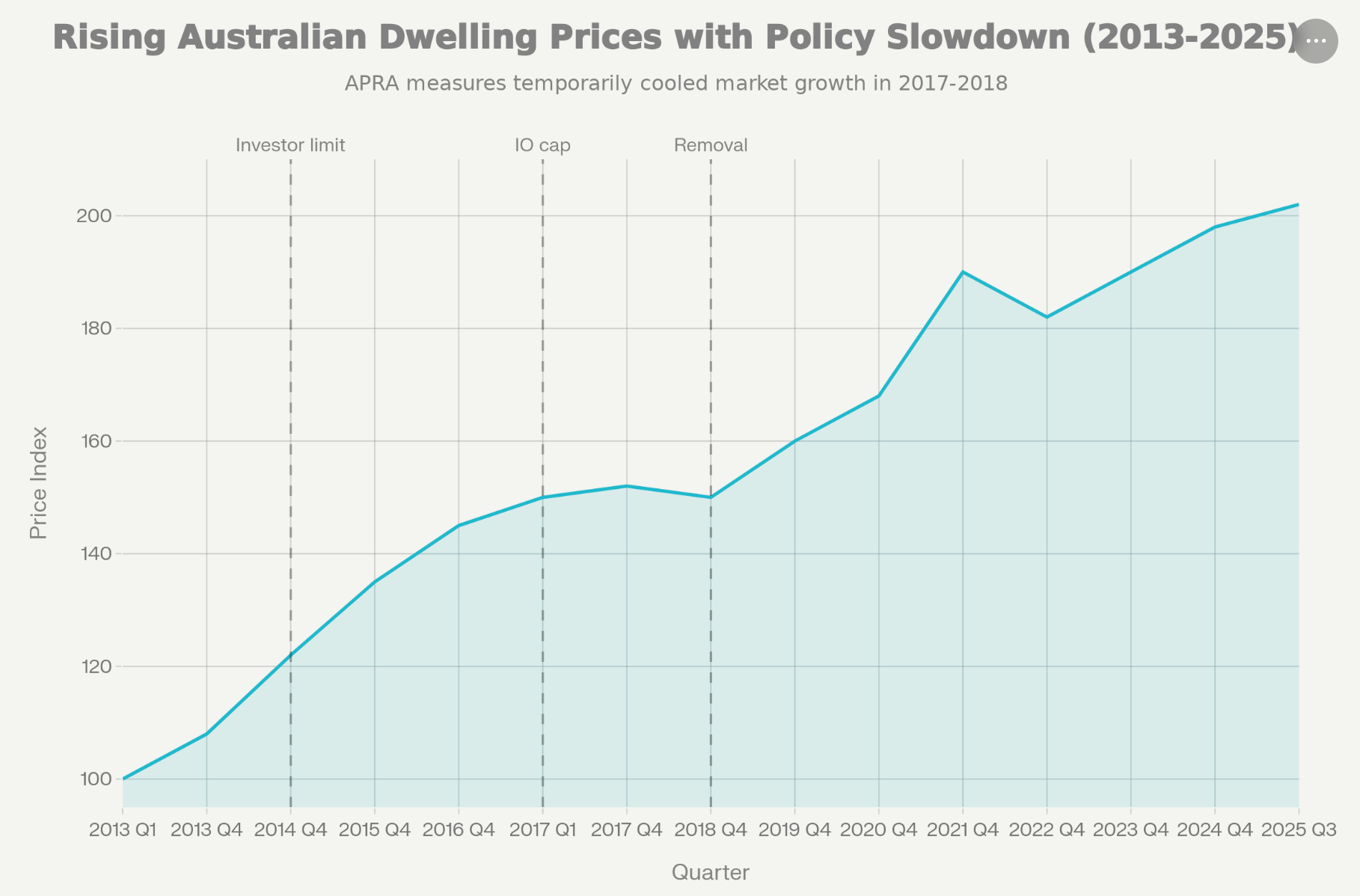

APRA’s new 2026 DTI cap is much softer and more targeted than the 2014–2018 investor and interest‑only interventions, so it is unlikely on its own to trigger a 2018‑style broad price correction, though it can still slow highly leveraged investor activity at the margin.

Evidence from the earlier measures shows that when APRA hit investor lending and interest‑only loans hard, investor growth and prices in investor‑heavy areas did slow noticeably, but the new DTI rule affects a much smaller slice of loans and explicitly exempts new supply.

What APRA did in 2014–2018

In December 2014, APRA imposed a 10% annual growth “speed limit” on investor lending at each ADI, directly constraining how fast banks could grow their investor books. In March 2017, APRA added a cap so that interest‑only loans could not exceed 30% of new residential lending, which especially hit leveraged investors and higher‑LVR interest‑only loans.

These were blunt, bank‑level volume caps: if a lender was running close to the 10% investor growth or 30% interest‑only share, it had to actively turn away business or re‑price and tighten standards, regardless of individual borrower DTI. APRA ultimately removed the investor growth benchmark in 2018 and later the interest‑only benchmark once lending growth had moderated and riskier segments had shrunk.

Evidence those measures slowed prices

Research cited by the BIS and RBA found that after the investor growth limit, regions with high investor concentrations recorded weaker housing price growth compared with more owner‑occupier‑heavy regions, consistent with investor demand being curbed. The Australia Institute notes that the 2017 macroprudential policies increased interest rates on investment loans, restricted investor demand and “reduced demand for housing and, in turn, the price of housing.”

RBA analysis of the 2014–2017 package concluded that the combination of higher investor rates, lending caps and stricter serviceability guidelines contributed to a cooling in Sydney and Melbourne price growth after the 2015–17 boom, even though low rates still supported the broader market. In other words, when APRA directly squeezed investor and interest‑only volumes, investor‑driven segments did slow and prices flattened or dipped in parts of the cycle.

How the 2026 DTI cap is different

From 1 February 2026, APRA will cap the share of new loans with DTI ≥ 6 at 20% of new lending (separate buckets for owner‑occupiers and investors), but today only around 6–10% of new loans sit above that threshold. Unlike 2014–2017, this is a guardrail on the riskiest tail of lending, not a broad cap on all investor growth or all interest‑only loans.

Crucially, loans for construction or purchase of new dwellings are excluded from the cap, so high‑DTI lending can still flow into new supply more freely. Commentary from analysts and brokers describes the new rule as “measured” and “pre‑emptive”, with domain‑level and industry views suggesting limited direct impact on prices, though it may constrain some high‑leverage investor strategies.

Will this DTI cap slow or drop prices like 2018?

Many commentators expect the direct impact on prices to be modest because:

- Only a small share of loans are above 6x today, so most borrowers and transactions are unaffected.

- Banks generally sit well below the 20% limit now, meaning no immediate need to cut lending; the cap mainly prevents a future surge in high‑DTI lending.

- New‑dwelling loans are exempt, preserving investor and developer access to credit for new supply.

By contrast, the 2014–2017 caps directly throttled investor volumes and pushed up investor and interest‑only rates, which clearly reduced investor participation and softened prices in investor‑heavy segments. The new DTI cap could still:

- Make it harder for heavily leveraged portfolio investors (DTI > 6) to keep expanding, thereby slightly damping demand at the margin.

- Provide a platform for APRA to add further measures (for example, re‑introducing investor or IO caps) if investor credit surges again, in which case the combined effect could echo 2018.

So on current settings, the new DTI limit is more of an early‑warning brake on risk, not a direct, market‑wide squeeze like 2014–2017, and by itself is unlikely to produce the same broad price correction that followed those earlier macroprudential moves.

At PB property we are always on top of what's happening and if you are confused and want to know if this might effect you get in touch.

share to